Afghanistan’s school deworming efforts – and the ‘missing million’ girls in need of treatment

By Ruchi Kumar

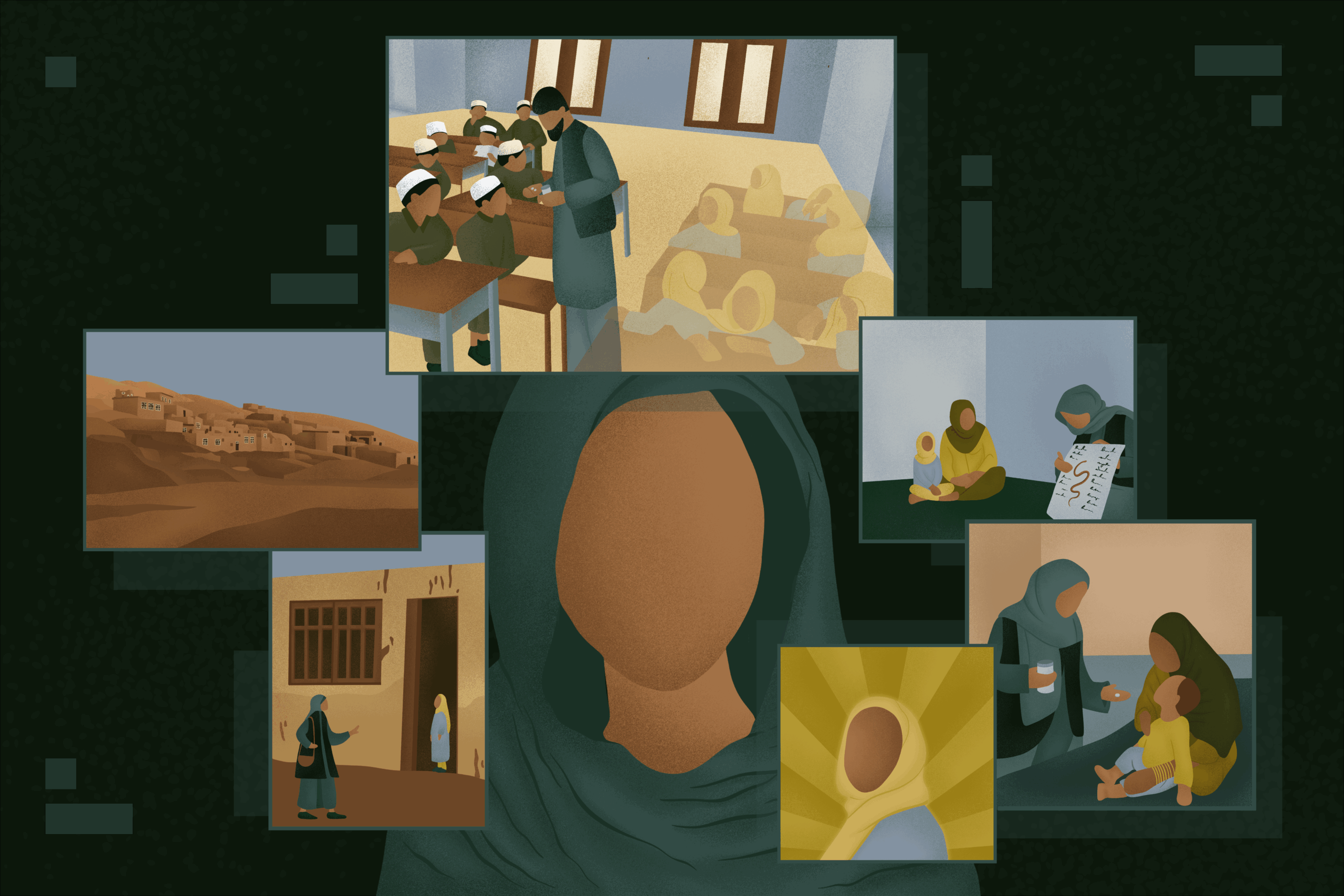

Fariba Sadat, 48, teaches math at a girls’ school in northern Afghanistan. She’s been an educator for nearly three decades, and during that time, she’s watched her country undergo conflicts and changes. But she’s remained steadfastly dedicated to her students, their education as well as their health and wellbeing.

It was this commitment to her students that led her to take on a new role at her school last year—as the administrator of the deworming programme to prevent intestinal worms in children.

“As a teacher it is my job to nurture and protect the children, and participating in this program is an extension of that because I can make sure the next generation of boys and girls are safe and healthy,” she said.

With a background as a trained midwife, Fariba took over the deworming program from another teacher who retired, and quickly immersed herself in training to administer the deworming pills, to ensure effective and wide coverage among students.

“I explained to the students that this medication was provided to remove harmful parasites from their bodies. And even answered questions and concerns parents had” Fariba said. “Some parents were concerned about the side effects of the pills. I assured them it was safe to take,” she added.

“In this way, we reached about 3,000 students,” she added.

Infection with intestinal worms can cause serious nutritional deficiencies, including anaemia, which is a grave risk to girls and women as it can increase their risk of complications in childbirth. Intestinal worm infections also damage children’s physical and mental development, which impacts their education. As alarming as it sounds, intestinal worms can be easily treated and prevented with a single deworming pill given to school age students once or twice a year, depending on prevalence.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that roughly 17 million people in Afghanistan, including 10 million school-age children, are in need of treatment for intestinal worms. The country’s deworming program, under the aegis of the WHO, has been operating for over two decades. Since 2016, the World Food Programme (WFP) has been leading the implementation of the program in collaboration with several partner organizations with funding from the END Fund.

“We work closely with several United Nations agencies, and also engage on the technical level with the Afghan Ministry of Public Health and Ministry of Education to promote deworming,” said Adeela Khalid, Head of Program for WFP in Afghanistan.

From raising awareness about the disease by providing parents with information to training teachers like Fariba in administration of the pill to its actual implementation, the deworming project is a massive undertaking, aiming to reach over 9 million Afghan children every year.

Navigating security challenges to reach children

Decades of conflict, widespread poverty and political instability in Afghanistan have created a challenging landscape for humanitarian work, and the deworming program is no exception.

“During the years of fighting, all public health projects were impacted, particularly in areas of conflict,” Khalid shared. Conflict would often force the temporary closure of schools—the ‘focal points’ of execution of the deworming program, impacting efforts. “However, as soon as fighting ended in a specific location, we would resume the program and work to reach out to those children who may have missed getting the pills due the conflict,” she shared.

When active conflict ended in August 2021, it became safer for health teams to access communities in need of treatment. It was a herculean task, but in their own enterprising ways, the deworming team managed to reach 93% coverage among Afghan school age children that same year.

“The most significant change since the end of the conflict has been improved access across the country, which allows us to implement and monitor the program in over 18,000 educational institutions,” Khalid said. Prior to 2021, about half a dozen different districts per year had not been able to be reached at all.

Girls are excluded from school and missing treatment

While access to the schools has improved following the end of conflict, the exclusion of girls of a certain age from schools across the country has impacted the deworming program’s reach. As a result, coverage levels for deworming school-age children declined from 93% in 2021 to 78% in 2023.

“Since 2021, we have not been able to reach an estimated 1.1 million secondary-school age girls,” said Khalid. This number is expected to increase as more girls graduate primary school each year, but are unable to continue their education.

This gap could threaten to increase cases of intestinal worms as the parasites are shed into the environment by infected people, and spread easily in areas where sanitation and hygiene are lacking. The Deworming Technical Working Group, that comprises all agencies and Afghan ministries involved in control efforts, is looking into solutions to reach all out-of-school children, including the girls excluded from secondary school.

“The issue of how to reach more school-age students, the girls in particular, has been one of the top agenda for every meeting,” Khalid said.

Years of navigating the challenging terrain has equipped the Afghan team to come up with unconventional approaches to problems. WFP and its partners are looking into new ways to reach parents and family members of young girls to raise awareness on the importance of getting the deworming pill.

“WFP works in health centers across the country to treat malnutrition, so that is an opportunity to reach and sensitize families,” said Khalid. “We are now also looking into the possibilities to connect the deworming program with our longer-term resilience programming. Especially when we work with women in the communities participating in vocational training, we see an opportunity to reach the families of out-of-school children and girls.”

Making a difference for Afghanistan’s children

As the deworming program continues to expand, Afghanistan can begin to assess its progress towards achieving its goals to eliminate the disease as a public health problem. A 2022 study of intestinal worm prevalence in Kandahar found a 39% overall prevalence of intestinal worm infection in school-age children included in the survey. This indicates that infection is likely to be high across the country, especially in areas where water, sanitation, and hygiene conditions are poor.

An updated nationwide survey is critically needed to assess the impact of the program on disease levels. The WHO recommends conducting impact assessments for intestinal worms every 2-5 years, but Afghanistan’s last assessment was in 2017 due to the challenges faced by the country. More resources are needed to support mapping efforts, which are crucial to focus treatment and other health interventions to areas of greatest need.

As an involved member of her community, Fariba has already noticed the impact of her work with deworming efforts in her classroom. “This program has been incredibly beneficial for students,” she said, citing examples of students who had shown symptoms which were cured on receiving the medicine.

“One student suffered from a bloated stomach. After taking the medication, his condition improved significantly,” she shared. “His mother later visited the school to express her gratitude for the treatment. It was a very positive experience to be able to make a difference,” Fariba added.