A different kind of homework: How Kenyan school kids’ toilet time is advancing elimination of neglected diseases

By Mary Mwendwa

Photography by Khadija Farah

How School-Based Deworming is Eliminating Tropical Diseases in Kenya

Uasin Gishu, Kenya – On a crisp, sunlit morning, a dedicated team of healthcare experts embarks on a mission of profound importance. They are mapping the spread of two of Kenya’s most persistent neglected tropical diseases—intestinal worms, also known as soil-transmitted helminths, and schistosomiasis.

As many as 5.4 million school-age children across the country require treatment for at least one of these infections. This silent epidemic impacts their health, cognitive development, and growth. These infections spread easily where there is a lack of quality sanitation infrastructure and clean water. Infected children may become too tired and ill to attend school and learn effectively, which limits their potential and perpetuates the cycle of poverty and disease.

This effort is part of Kenya’s nationwide prevalence survey of intestinal worms and schistosomiasis. Schools across different regions are selected for participation, with pupils providing samples of urine and stool to assess the prevalence of these infections.This survey is not just about collecting samples—it is about securing the future of Kenya’s children. By analyzing data from students, researchers can determine the true burden of intestinal worms and schistosomiasis, assess the effectiveness of current interventions, and refine strategies for greater efficiency.

Without accurate prevalence data, children in high-risk areas may not be treated, while treatment may be conducted unnecessarily in areas at low risk. Uasin Gishu County is one of many areas undergoing rigorous evaluation to fine-tune these efforts.

The Role of Sanitation and NTDs Prevention in Schools

A quiet hum of learning fills the air of the school grounds as the survey team arrives, led by Julius Kalenda, Deputy Director of Medical Laboratory Services with the Kenya Ministry of Health. Accompanying him are laboratory technicians and staff from Uasin Gishu County Referral Hospital, Kilifi County Referral Hospital, and Amref Health Africa. They are all determined to collect crucial data that could result in life-changing health interventions for these youngsters.

This team is one of eight conducting the survey in Uasin Gishu Sub-county. The team visits 15 schools, collecting samples from 30 pupils at every school. It is a rigorous job to travel the expansive terrain to visit different schools in the villages. In a day they are able to visit three schools, and then in the evening, they head to the laboratory where they work late to analyze stool samples.

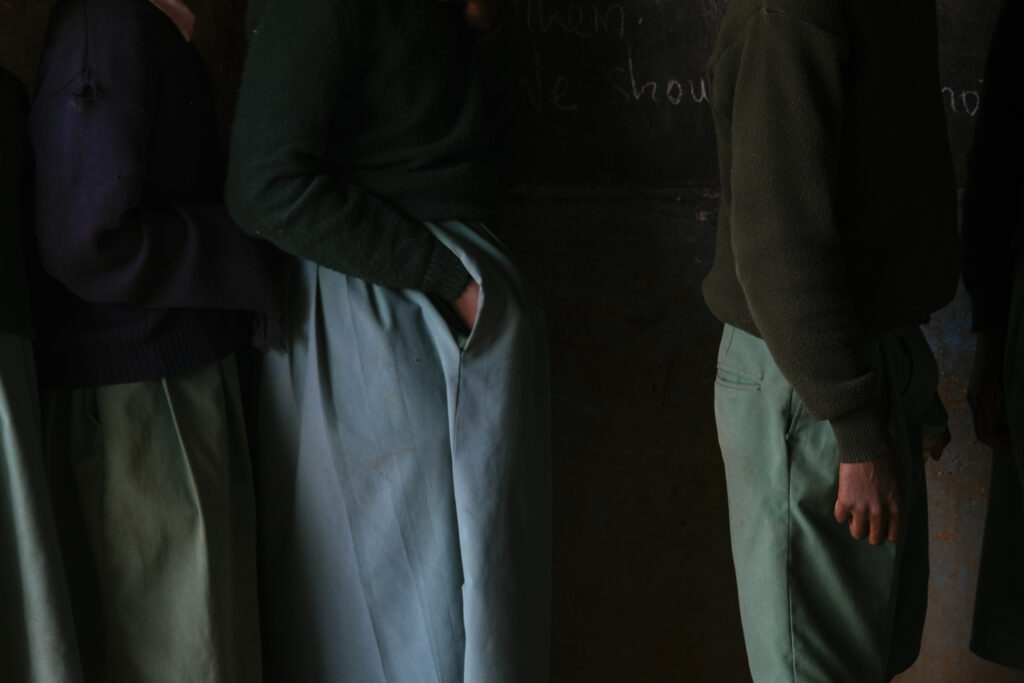

Thirty students, evenly split between boys and girls aged 8 to 14, are chosen for the study at their first stop, Kerita Turwet Primary School. They are briefed on the importance of their participation—how their small contribution could help protect millions of other children from these debilitating infections. Some students look curious, others nervous. One boy hesitantly shares that he has never participated in such an exercise. “I am nervous,” he says, “But the doctors told us this is important because they want to know if we have intestinal worms or schistosomiasis.”The collection of stool and urine samples takes about 30 minutes. One by one, the children return with their samples—boys carrying their containers openly while the girls discreetly tuck theirs into their uniform pockets. Each sample is carefully labeled using barcodes to maintain accuracy and confidentiality.

Despite their efficiency, the survey team faces challenges. “This is a delicate and sensitive survey,” Kalenda explains. “A small mistake could compromise the accuracy of our results. And some pupils struggle to produce stool samples.” Kalenda oversees the handling of stool samples, which will be delivered to the laboratory for analysis. Silas Keter, a laboratory technician, takes charge of urine analysis using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A mobile PCR device is used to detect Schistosoma DNA in the urine samples, and is a highly sensitive and specific method. Keter does this analysis immediately following sample collection while at the school to avoid any pH changes in the urine during transport to the lab which would affect the outcome.

Immaculate Onchari, a research assistant, sits at the corner in a classroom with a smartphone loaded with a questionnaire. She is the last person the pupils see after giving out their samples and having their data recorded. She is asking questions about knowledge on intestinal worms and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) conditions at home. “Mnatoa wapi maji ya matumizi nyumbani, Where do you get water for your household?” Onchari poses a question to one of the pupils, a girl. “Huwa tunachota maji kwa kisima, we usually fetch water from a well,” she responds shyly, looking down and folding her hands.

“I use English and Swahili for the questionnaire,” says Onchari, noting that at times there is a language barrier. “When I realize a pupil is struggling to respond I engage a teacher to help, teachers always help and they can tell which language is best for certain pupils in a school.”Kerita Turwet Primary School pupils come from a nearby community where they predominantly speak Kalenjin. In school, they speak Swahili, and English is not a first language for most.

Scholastica Kipkoeach, a sanitation teacher who also oversees WASH projects at the school, plays a crucial role in coordinating the pupils and maintaining records. She ensures the school has hand washing stations, which are important for preventing the spread of schistosomiasis and intestinal worms. Her school has never participated in such a survey before, but she recognizes its importance. “This exercise is beneficial because it ensures our students are healthy. A healthy student learns better,” she states.

She also highlights the need for mental preparation. “These children come from different cultural backgrounds. It’s essential to explain the process to them beforehand so they understand why it matters.”

You see, these pupils come from different religious groups, I know of parents who never want any sample of their children taken, they believe it is a cult-related activity. Such parents usually need a lot of explanation and assurance that the samples collected are purely for medical reasons,

Kipkoech explains.

Laboratory Testing Validates School-Based Deworming Success

After sample collection, the work continues at Uasin Gishu Referral Hospital’s laboratory. Henry Maleka, a laboratory technician, emphasizes the crucial role of the laboratory in their work. “Most of our work happens in the lab,” he says. “Here, we process samples for intestinal worms using a technique called Kato-Katz. It’s an effective method for detecting parasites like hookworms and roundworms. The process takes time, but once the slides are prepared, we examine them within 30 minutes to an hour.”

Looking into the microscope to see if there are any intestinal worm eggs on the slide, Maleka says, “This is an exercise that needs trained personnel and investments in the laboratory.” This hospital is well-equipped to analyze and process the survey results, but this capacity is not available across all of Kenya, or in other countries where neglected tropical diseases are endemic.

Moreover, with the decline in infection prevalence, there is an urgent need for research and development of more sensitive, cost-effective, and field-friendly diagnostic tools. Current methods like Kato-Katz have limited sensitivity in low-intensity infections, and while PCR offers higher accuracy, it is too resource-intensive for widespread use. Advancing diagnostic innovation will be crucial for ongoing surveillance and targeted interventions in Kenya’s journey toward eliminating intestinal worms.

This Survey Provides Crucial Data for National Health Policy on Sanitation and NTDS

As the survey team leaves Kerita Turwet Primary School, there is a sense of purpose in their work. The data collected today will inform tomorrow’s health policies, ensuring a brighter, healthier future for Kenya’s children.

In line with the Kenya National Neglected Tropical Disease Master Plan 2023–2027, the country has scaled up interventions to accelerate progress toward the elimination of soil-transmitted helminths and schistosomiasis as public health threats. Accomplishments include attaining high coverage of school-age children with treatment, and expanding community-wide treatment in 15 counties to include both preschool-age children and adults. As a result, Kenya has significantly reduced infection rates over the past decade. According to the WHO, the number of children and adults requiring treatment for schistosomiasis decreased by almost 8 million people, and the number of school-age and preschool age children requiring treatment for intestinal worms decreased by 3.6 million.

However, sustained action and continued investment are critical for long-term success. Prevalence surveys like this one ensure that progress is measured, gaps are identified, and health programs are adjusted for maximum impact. More funding is needed to treat newly identified endemic areas, expand treatment to adults, improve WASH infrastructure, and support behavior change efforts that are critical to sustaining gains. Health systems and surveillance mechanisms must also be strengthened to enable routine treatment delivery through community health structures.

The work ahead is considerable, but Kenya is equipped for the challenge. Julius Kalenda noted that Kenya’s Ministry of Health considers this survey a game-changer. “We lacked a comprehensive baseline for the entire county,” Kalenda explains. “Without knowing the prevalence of intestinal worms across different areas, we can’t effectively target interventions. Now, with evidence in hand, we can ensure that treatment reaches the right places and resources are used wisely.”

Students laughing as Julius Kalenda explains the purpose of the survey. Photo by Khadija Farah.

About The END Fund’s Role in Kenya’s Deworming Programs

The END Fund in partnership with Amref Health Africa and the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) provides support to the Kenyan Ministry of Health to conduct mass deworming campaigns to treat intestinal worms and schistosomiasis, with more than 57 million treatments delivered for both diseases to date. Through the Deworming Innovation Fund, the END Fund is working with four counties to demonstrate the feasibility of interrupting transmission, offering a proof of concept for wide-scale elimination efforts in Kenya and beyond. The ARISE Fund is supporting treatment in 11 counties to accelerate elimination of intestinal worms and schistosomiasis as a public health problem. The END Fund also supports complementary initiatives such as water, sanitation, and hygiene improvements, enhanced coordination for neglected tropical diseases, and behavior change communication to help break the transmission cycle.