One man’s work saved thousands of lives in Uganda and now a renewed strategy aims to eliminate a deadly parasite

East Africa is the next frontier in the effort to end visceral leishmaniasis

By Greg Porter

His motorcycle was humming along a dirt road on a dry, hot day in Karamoja when he saw a man off to the side waving at him to stop. He released the throttle, slowly bringing the bike to a halt.

Andrew Ochieng is an imposing man with an inviting smile. He is built large and strong. He rides a white Yamaha that looks small underneath his massive frame. It is a unique motorcycle for this area of Uganda, and people have learned to identify him coming by the sound of its loud engine.

As the dust settled, Andrew greeted the man in one of the seven languages that he speaks. The man began to explain how one of his neighbors was sick with symptoms that might be visceral leishmaniasis, a deadly parasitic disease that is common in this area. This happens frequently for Andrew.

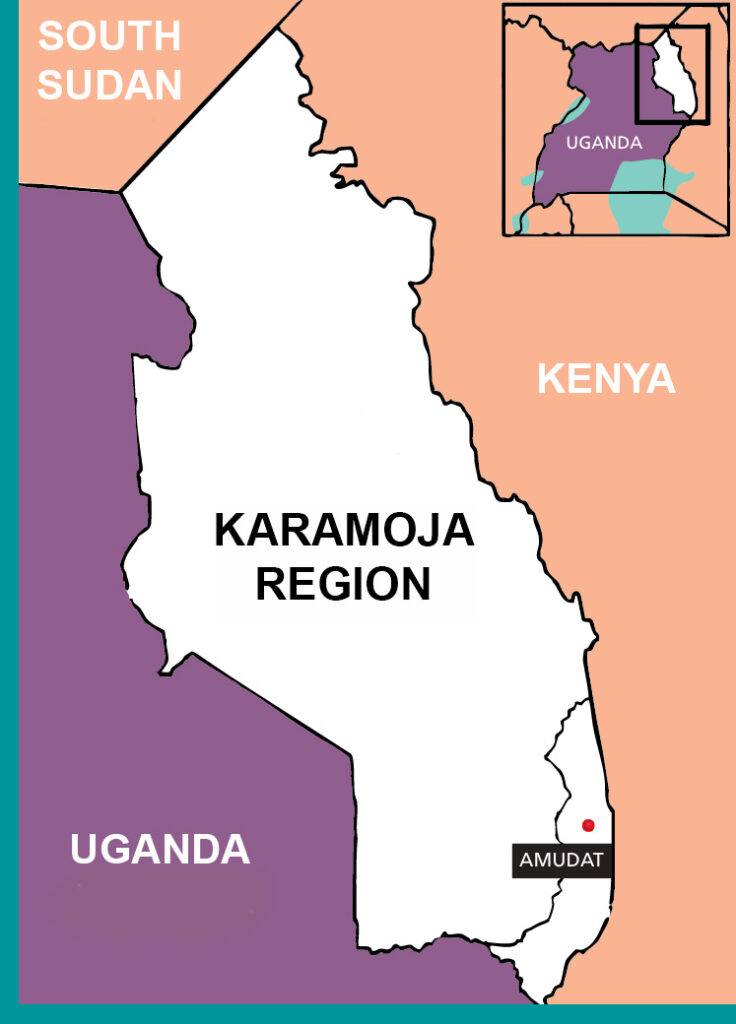

It’s Andrew’s job to search for people who may have visceral leishmaniasis in the rural regions of northeastern Uganda. This parasite spreads by sandflies that nest in Karamoja’s arid climate. If left untreated, the disease slowly kills nearly everyone who develops symptoms.

The sheer scale of finding people with visceral leishmaniasis is a daunting task—Andrew can spend nearly a month out searching for patients, living amongst the nomadic communities, sharing their meals, and sleeping with them in the open.

He rides his motorcycle on the labyrinth of trails connecting communities made up of cylindrical clay houses with grass roofs, traveling up to 2,400 kilometers on unpaved roads each month. In this volatile area, communities often position their homesteads down paths with several dead ends to hide themselves from cattle thieves and the military.

“I never use a map. The map is in my head,” Andrew stated matter of factly, because in reality there are no maps of the roads he takes.

Quickly finding treatment drastically improves a person’s odds of surviving, but accessing the specialized treatment required for visceral leishmaniasis in this region is anything but easy. The other critical side to Andrew’s job is helping patients reach health centers, which can be more than a day’s walk from their secluded homesteads.

Dr. Patrick Sagaki is the head of Amudat Hospital’s visceral leishmaniasis clinic in southeastern Karamoja. He explained just how important Andrew’s job really is: “ Andrew basically lives with these people most of his time. He is moving from place to place looking for people [with signs of visceral leishmaniasis], trying to organize them, to collect them to one center where the vehicles come and get them for referrals to the hospital. When there are many, he remains with them. He drinks with them. He stays with them until they collect all the patients. After treatment he brings them back to their loved ones,” said Dr. Sagaki.

It is estimated that Andrew has found nearly 10,000 patients with visceral leishmaniasis in his nearly two decades of work. “If Andrew was not around, we would have so many community deaths because of visceral leishmaniasis,” said Dr. Sagaki. Without treatment, the fatality rate is almost 100 percent for visceral leishmaniasis.

“Everyone must work. Everyone must sweat to earn a living,” Andrew said, downplaying the difficulty of his job.

Navigating cultures and conflict

Finding and treating people with visceral leishmaniasis is further complicated by the interplay of nomadic movement, cultural identities, and conflict amongst the 1.3 million people who live in this part of Uganda.

The majority of people in the Karamoja region are cattle herders, called pastoralists. They are often on the move across borders, following the weather patterns to ensure there is vegetation for their cattle to graze. The pastoralists of Turkana, an area within Kenya, can travel several hundred kilometers per year, passing through South Sudan, Uganda and Kenya. Their movement can also further the spread of visceral leishmaniasis, as the parasites travel in an infected person’s bloodstream and can be transmitted via the bite of sandflies to other communities.

Cows, the source of wealth for pastoralists, are also a point of conflict. One cow can go for the equivalent of several hundred US dollars at the market, and thieves often try to steal cattle from other tribes. People stay on edge against theft, and boys sleep outside next to their herds as protection from would-be cattle thieves, putting them at further risk of infection by proximity to livestock and sandfly bites.

These risks are compounded by the area’s strenuous relationship with the Ugandan military. The tribes are still wary of any interactions with the military and outsiders who they may suspect to associate with the military.

Trying to gain entry can be dangerous. Andrew relies on his deep knowledge of the local tribes and languages, and the relationships he has built with them over 20 years of work. “First thing is important, people must trust you. If they do not trust you they will just tell you to get lost,” Andrew explained.

“There are many ethnic languages here,” Dr. Sagaki explained. “Andrew speaks to them very fluently. That is why he can walk into these volatile communities freely without any problem. He has never been shot at because they know him as a savior of lives.”

“ I’m only scared with somebody who I have not seen,” Andrew said. If he is able to talk with a person face to face, he knows that he can make them understand who he is and the importance of his work.

On a recent trip, Andrew was traveling back to the hospital with patients in an ambulance. He knew that someone was shot and killed on the same road just a few days prior. As they approached a turn, his driver noticed two young men on the side of the road, holding guns. The driver wanted to turn around, but Andrew insisted on moving forward and speaking with them. The patients needed to get to the hospital.

The armed men stopped the car and said they were there to provide security. Security for who and by who? Andrew wondered, but did not ask. It wasn’t important to know in order to pass them safely.

“ I just told them, ‘Okay, thank you for providing us security. Have some water. I have some biscuits.’” Andrew handed over two packs of biscuits and two bottles of water, but then a few more boys from the bushes showed up.

“So, I had to exhaust the water we had inside.”

With the armed men placated, the ambulance proceeded past the makeshift checkpoint and safely delivered the patients to care.

Dr. Sagaki described Andrew’s skill at navigating this conflict with admiration. “At times where there is insecurity, we fear for him. We even cautioned him not to go there. But he will come back telling you he was there, he met [members of fighting tribes and members of the military]. They greet him and let him go because they know what he’s doing.”

The stakes are deadly

Andrew intimately understands the importance of his work because more than two decades ago, during his adolescence in Karamoja, he found himself in the same clinic as the patients he helps today. Like many of his patients, Andrew was sick for months and no one could figure out why. His parents turned to traditional medicine, utilizing a technique of cutting and burning his stomach to reduce the swelling, to no avail. Finally, a neighbor familiar with visceral leishmaniasis who knew of a clinic operated by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to treat the disease implored the family to seek care. After a month in the clinic, Andrew was cured and he soon found employment with MSF searching for other people suffering from visceral leishmaniasis.

In November 2024, there were sixteen patients in the visceral leishmaniasis clinic in Amudat, now run by the Drugs for Neglected Disease Initiative or DNDi. Established more than 60 years ago by MSF, this clinic was the only one in the border region with Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan, providing a lifeline to patients.

The modest rectangular one-story building offers two shared rooms for patients and an office for hospital workers, separating the two rooms. Children roam throughout the clinic, coming freely in and out of the office as the staff go about their work.

“They are here all the time,” said Chebjira Priscilla, 29, with a smile. She has been a nurse at the clinic for four years. “They like when we tell them stories.”

Lokel, a six-year-old girl from a tribe in Turkana, was in the clinic receiving treatment for visceral leishmaniasis. This was the second time she’s been treated at the clinic—after the first round of treatment, her illness came back. A small percentage of people relapse with the disease, but young children are more at risk.

Andrew found Lokel during a routine visit to her village, which is about 200 kilometers from Amudat. Normally with just one patient, Andrew would try to transport them on his motorcycle, but Lokel was too sick for the strenuous journey. Andrew traveled half a day back to Amudat to arrange for the local ambulance. They set out the next day to return to Lokel’s village and bring her to the clinic, a round-trip of more than twenty hours over very rough terrain. Lokel’s mother had recently given birth and was unable to accompany her daughter to the clinic, so her young aunt, Amana, traveled with her. Patients, especially children, need to be accompanied by a caretaker because the clinic does not have the staff to provide non-medical care for patients.

“This is the proof that communities have put their trust in Andrew”, explained Dr. Sagaki. Parents will often trust Andrew to travel hundreds of kilometers with their sick children because they’ve learned that he is their lifeline to the visceral leishmaniasis clinics.

“She was very weak when she came in,” said Andrew, referring to Lokel’s severe anemia, “Whenever I see a patient who has a problem with anemia, I have to save that one’s life first.”

Anemia is a sign that the patient is gravely ill; it results from the parasite that causes visceral leishmaniasis attacking the bone marrow and spleen, which are responsible for blood cell production. People with visceral leishmaniasis also suffer from uncontrolled bleeding due to a lack of platelets that help their blood clot.

A week later, Andrew was in the clinic again to see Lokel and Amana. The effects of the treatment were powerful. In contrast to the desperately ill child he first met, Lokel was happy and playful, laughing as Andrew greeted her in the clinic.

“What is so rewarding is you really see the difference between when patients come in and leave,” said nurse Priscila. “They really improve because of the treatment, and also the nutritional assistance we give them.”

For patients like Lokel, underlying immune-compromising health problems can make them more vulnerable to becoming deathly ill with visceral leishmaniasis. The trick of visceral leishmaniasis is that it takes advantage of a weakened immune system stemming from other conditions, such as HIV, malaria, or malnutrition. The disease moves slowly, and symptoms may be mistaken for other illnesses that cause fevers. Combined with the difficulty in reaching the clinic, this often means that patients may only seek treatment once they are already in critical condition.

However, if patients can be found and treated quickly, their odds of survival greatly increase. In addition to life-saving medicine, patients need healthy meals to build their strength to fight off the infection, and blood transfusions are frequently required.

“Patients who are very sick need to go to the hospital as fast as possible. Patients who have anemia need blood right away,” Priscila explained.

Lokel was found in time to save her life. For some patients, help can come too late.

During a routine daily treatment in November, a team of two nurses moved diligently between the beds, injecting patients with the precise combination of medication needed over the three week treatment period to kill the parasites in their blood system. Kezi Lowot, a medical clinician, noticed one man lying motionless in his bed. He had been agitated the night before, moaning and falling out of bed.

Calmly, Kezi began to check his vital signs by hand. There are no machines to continuously monitor a state or raise the alarm if a patient’s heart rate drops dangerously low or stops beating altogether. The clinic is too short-staffed for a clinician to stay with each patient constantly, no matter how ill they are. Kezi forcefully rubbed his sternum, a last attempt to see a sign of life and called over a doctor to confirm that the man had died.

He came into the clinic in a severe state two weeks prior, alone and emaciated. With no family around, he was working at a nearby mine—a strenuous job that can exacerbate the symptoms of a disease like visceral leishmaniasis. A shortage of donated blood meant that he wasn’t able to receive a full transfusion, an unfortunate but frequent occurrence.

Dr. Sagaki, the head of the clinic, spoke with Andrew about trying to find the man’s relatives to let them know of his death. Andrew didn’t know where his family might be. The clinic staff quickly arranged to bury him on the hospital grounds.

The man was the first patient to die in their clinic in nearly two years, a stark reminder of the importance of finding patients quickly, and of the gaps that still remain in the health system’s capacity to provide this vital care.

Attention turns to a strategy of elimination

While Andrew is focused on the daily life-saving work of getting people to the hospital, a group of public health partners have built the strategy to tackle visceral leishmaniasis in East Africa.

In June of 2024, the World Health Organization gathered East African visceral leishmaniasis experts to discuss a new way forward to eliminate the disease as a public health problem. Achieving ‘elimination as a public health problem’ means that cases of visceral leishmaniasis will become extremely rare and very few people will be infected, though continued surveillance would be needed to ensure the disease doesn’t resurge. The experts gathered by the WHO examined recent successes in eliminating visceral leishmaniasis on the Indian subcontinent to develop a tailored approach to the East African context.

In 2005, Nepal, Bangladesh, and India signed a memorandum to cooperate in the effort to eliminate visceral leishmaniasis. Since then, the Indian subcontinent reduced the number of cases by 95%, and Bangladesh became the first country in the world to eliminate the disease as a public health problem. Bangladesh achieved this milestone through a combination of outreach to communities, aggressive efforts to control sandfly vectors, and enhanced drug protocols tailored to the population.

“To make significant gains against visceral leishmaniasis in East Africa, research and innovation is critical to find faster diagnosis, better treatments and improve our understanding of how the disease spreads,” explained Simon Bolo, head of the Leishmaniasis Access program for DNDi in East Africa.

The Ministry of Health in Uganda has partnered with DNDi and the END Fund to adapt Bangladesh’s strategy to the realities of the disease in Uganda. First, this requires a better sense of where the disease is spreading, and how.

“We will need to ramp up case finding,” said Ivan Ankunda, the head of the visceral leishmaniasis unit for the Ugandan Ministry of Health. However, resources are limited to support case finders like Andrew across the region. “ That’s why we have only Andrew,” explained Dr. Patrick. “Otherwise we could have [someone] in every district, just like Andrew is doing. I think we could reach many, and save many more lives.”

While Uganda has treated visceral leishmaniasis for more than two decades, it is still unclear just how widespread the disease really is. A recent study found that roughly 5% of the population could be living with visceral leishmaniasis. The study is good news in that it confirms the country is close to reaching a threshold of eliminating the disease as a public health problem, but it also highlights a different concern. The most common risk factor for people being infected is a lack of knowledge about the habitat of the sandfly, the vector responsible for transmitting the disease. Study respondents who didn’t have knowledge of sandfly habitats were five times more likely to be infected with visceral leishmaniasis than those who did. This may be because if communities aren’t aware of the risks posed by sleeping or traveling near sandfly habitats, they may not know to take precautions.

However, just what precautions will have the greatest protective effect against infection are unclear because there is a lack of knowledge about East African sandflies, and what preventive measures are most effective.

“Most of our strategy still relies on knowledge from India. We spray inside people’s homes to kill the sandfly because it was effective in India, but we don’t really know if it is the case here.” Ivan referred to the fact that sandfly species that avoid the inside of homes may not be well-controlled with indoor insecticidal spraying. Since many pastoralists sleep outside during the dry season, a more effective strategy may include spraying outdoor fences to create a barrier against the sandfly around these sleeping areas.

There are 14 different types of sandfly in the Karamoja subregion alone. Identifying which of these species spread the disease, their behavior, where they breed, and how they feed, and what environmental and climate patterns affect their populations is crucial to develop an effective vector control strategy and to give people the proper information on how to avoid the disease.

“[We must] begin to attack the vector [sandfly] to really achieve elimination,” said Dr Ivan Ankunda.

Uganda will begin to capture sandflies in order to map the disease more precisely, providing a better understanding of where infections are occurring, and which sandfly is spreading the disease. Until recently, most of the studied sandflies came as a byproduct of malaria control teams capturing mosquitos and inadvertently capturing sandflies. With this information, the Ministry of Health will be able to target hotspot areas with more active case searching, and invest in treatment facilities where they are needed most.

“Visceral leishmaniasis is an enormous threat to the people of this region who live on the margins of the established health system. Everyone deserves to live a healthy life and we are committed to continue our efforts so that these communities no longer live with the threat of this deadly parasitic disease,” said Simon Bolo.

In 2025, the Ministry of Health is adding two more clinics in eastern Uganda to test and treat people for visceral leishmaniasis. “The clinics will reduce the amount of time it takes for people to reach treatment, so hopefully more people will seek out care,” said Ivan.

If there is enough attention and energy, people with visceral leishmaniasis can be found and treated, and the spread could stop–but for now resources remain limited. For Andrew, he will continue to be on the trails searching for his next patient to save.

Your support can ensure that we are able to continue providing life-saving interventions to those affected and strive towards a world in which no one’s life is threatened by devastating yet preventable diseases.s

Fact checking and editorial support by Duncan Duncan Ochol and Kebron Haile

Web design by Tracy Moige Mongare